Wabi and Japanese Watches - A GMT+9 x G-Peopleland Collaboration

By Bryan Anderson and Sjors

Sjors' note:

I have a friend who has a bit of a cleaning mania. She also tends to throw away everything she doesn't like at that moment. Once I went to her apartment and found only a shopping cart. It was propped open so it could be used as a chair. The walls and floor were totally white. She regularly visits us. She always says it's so nice and cozy in our house. I'm very uncomfortable when it isn't a bit untidy in the house.

When I really started collecting G-Shocks around 2001, I bought a lot of them secondhand. I enjoyed cleaning them and did not care about the stains, scars, and other signs of wear, as long as I could see the time. G-Shocks are made for use, so the use may show. In spring 2006, a member of the G-Shock forum showed a typical used G-Shock with a clear, see-through case. These models turn yellow or green when they are worn for a long time. I think Casio deliberately makes these models like this, often found in the G-Lide and I.C.E.R.C. series. At that time Bryan told me about wabi-sabi for the first time. It was amazing. Wabi-sabi could be interpreted in a lot of our everyday life and culture. I bought a very beat up Gaussman, which I really love (pictured above). Now I can give this Gaussman with battle scars a place.

I asked Bryan to write an article for me for my website. He immediately agreed, but somehow it became a long-term project. In all the communication we had about various things, it was like a red thread and the bottom line. For some time we lost contact, but fortunately Bryan is back (and how). Finally it's here, a GMT+9 x G-Peopleland collaboration article.

Wabi and Watches

Writing about wabi is a bitter challenge. It's similar to trying to define "soul."

Watch collectors with moxy sometimes spit out the term

wabi when discussing watches. It's not easy to use foreign words with

precision. I'm gonna attempt serve up a tasty explanation of the term that fills

in some of the nuances of its use, and tie my comments in with collecting

Japanese watches. Bon appetit.

What is Wabi?

The 17th century Japanese haiku poet Matsuo Basho coined the term wabi. The word means something like "loneliness" or "forlornness." A few years back watch collectors started using the term wabi when talking about dirt, grime, and discoloration that old watches acquire. But wabi is not synonymous with crud. Wabi is better thought of as the feeling of sorrow, often felt when looking at something ravaged by time.

Wabi is not a word on the tips of most Japanese people's tongues. In Japan, the word is mainly used in the rarefied world of the tea ceremony, and in literati circles. Most Japanese people don't pretend to understand the meaning of wabi, or feel they have the ability to use the word correctly.

Soetsu Yanagi, the father of the Japanese folk crafts movement, wrote about this in his book The Unknown Craftsman; A Japanese Insight into Beauty. Yanagi suggests that for most people, the word shibusa (the noun form) is a better term than wabi. That's because "the word wabi cannot be demonstrated by physical sense; it must be conveyed by formless spirit," Yangi writes.

The word shibui (the adjective form) is a common term in Japan, used by people every day. Yangi writes:

Wabi and shibusa, then, stand for the same thing. But whereas the word wabi belongs to the vocabulary of the select few, shibusa is overheard in the common parlance of the masses.

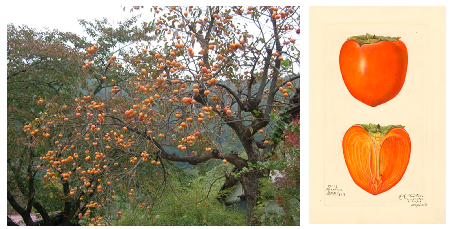

Shibui means different things according to context, including: old, old fashioned, dull (as in muted colors), cool, dry, and bitter. The meaning of the word can be tasted in fruit from Japanese persimmon trees. There are two types of persimmon trees (kaki no ki) in Japan, non-astringent (amagaki = sweet persimmon) and astringent (shibugaki = bitter persimmon). Plucked from a tree, the fruit from shibugaki is so tart one's throat tightens up and it's impossible to swallow. But cut it into slices and hang it on a string in the sun, and over time the fruit becomes sweet and delicious.

It is the same with our watches. Used daily our watches collect scratches, dents, and scars that weather them. It's bitter to scratch a watch, but it's sweet years later to see a scar and remember the fishing trip one was on when it happened. That's a shibui feeling.

Wabi in the Western World?

The insight that things acquire beauty through use isn't uniquely oriental. Henry David Thoreau and Basho were like-minded souls. Writing about one of life's necessities -- clothing -- in Walden; A Life In The Woods, Thoreau observed:

Kings and queens who wear a suit but once ... cannot know the comfort of wearing a suit that fits. They are no better than wooden horses to hang the clean clothes on. Every day our garments become more assimilated to ourselves, receiving the impress of the wearer's character, until we hesitate to lay them aside ... No man ever stood lower in my estimation for having a patch in his clothes ... I often test my acquaintances by such tests as this -- Who could wear a patch ... over the knee? Most behave as if they believed that their prospects for life would be ruined if they should do. It would be easier for them to hobble to town with a broken leg than with a broken pantaloon.

Just like our clothes becomes more a part of us each time we wear them, so it is with our watches. The bumps and bruises they pick up over time become a record of our lives. Sort of like the lines on our faces as we age. That is what makes them, and us, unique. We may long for youth, for unmarred beauty -- but the imperfections add a quality of shibusa, or bitterness, that looked at the right way is paradoxically sweet.

It's easy to be glib about this, but the proof is in the pudding. I once sold a recently purchased Grand Seiko I hit against the edge of a glass door and deeply scratched. The episode left a psychological scar, and I couldn't bare to look at the watch. Things are complicated in reality.

Dr. Wayne Lee, founder/owner of the Seiko Citizen Watch Forum (SCWF), once wrote that he could recall every scratch the case on his beloved Grand Seiko (pictured above) picked up over the years. He said each scratch had a story. When he sent the watch into Seiko Japan for servicing, watchmakers buffed all the scratches out of the case. Reading about this on the SCWF in 2003, I imagined I could sense mixed emotions in Wayne's words:

Today, I received my 9S55 GS that was sent to Katsu Higuchi for service. Seiko Japan has done a good job. It has gone through an overhaul, case and bracelet polishing and my beloved watch that has been with me for the last 4 years looks almost 95% mint. All the scratch marks that have their stories on the watch are no longer visible.

In contrast, Wayne's good friend Seiya Kobayashi has an Alba military watch he used for a decade while working in Tokyo as a television producer.

The watch was put through the mill. Seiya said he wore it during the day on camera shoots in freezing Hokkaido weather, and at night it soaked with him in molten hot spring baths. I think this watch is shibui. If Seiya had changed the glass crystal, or had the case buffed to remove the scratches, it would have lost as much as it gained.

Conclusion

This article has only scratched the surface of the topic of wabi. There is so much more to say. For instance, it's only slightly touched on topics like humility and uniqueness, both essential elements of wabi. At the very least, perhaps it's provided a small taste of what this Japanese term means.

###